Pine: The Pollen with a Bad Rap

Pine: The Pollen with a Bad Rap

Written by Dr. Joel Gallagher, Allergy and Asthma Center of NC, Cone Health Medical Group

Ahhhh… the sweet smell of pine. The smell of the winter

holiday season. The smell of that quintessential cleaning solution that my mom

used to clean just about anything around the house when I was growing up. Pine

definitely brings me back to where I grew up in northern Louisiana. Pine trees

were everywhere (including several 100+ year old pine trees in my own backyard). The names of establishments around my hometown literally began with “Piney

Hills” (Piney Hills Golf Course, Piney Hills Tackle Shop, etc.). Pine trees are

a big part of my new home here in North Carolina as well, although hardwoods

tend to be more prominent in the Piedmont Triad.

It was always taught during my fellowship and all board

review books that pine (member of the genus Pinus)

is a non-allergenic pollen. Although it gets a LOT of the blame for spring

allergy symptoms (at least where I grew up in the piney hills region of

Louisiana) since it tends to be the predominant pollen that covers everything,

its large size and low overall protein level are thought to be a minor actor in

the allergenic theater of our lives. Its proteins are also encased in a waxy,

hydrophobic (think fat-containing) layer that prevents its protein from

releasing into the surrounding tissues.

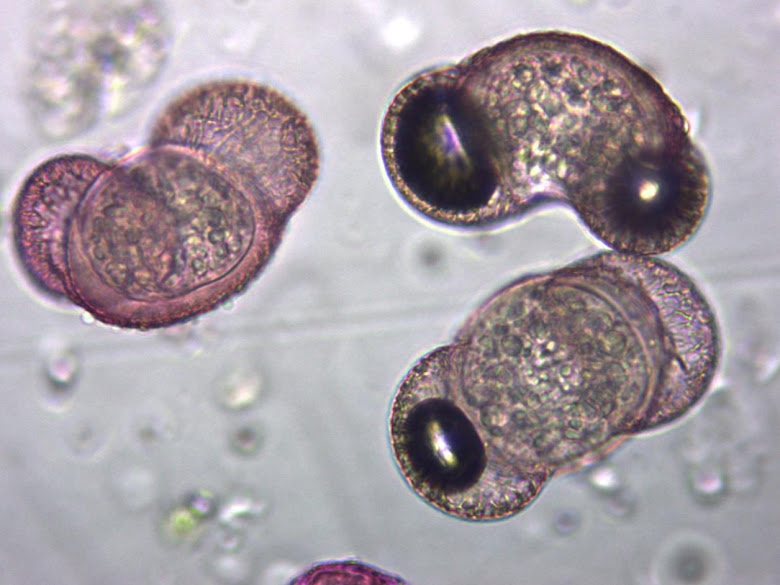

Image 1 (taken by Forsyth County staff on April 8, 2025):

Three pollen grains from the pine family shown under a microscope at 40x

magnification. The pink color is from a dye called Calberla’s stain that is

used to make pollen grains easier to see for counting and identification. Pine

pollen is larger than most other pollen grains, ranging from 60-100 microns in

diameter.

Its non-allergenic label is so engrained that pine pollen is

often used as a NEGATIVE control in nasal and bronchial challenge tests in the

clinical setting. This long-held belief might not always be the case, however. There

is some cross reactivity between pine pollen and grass pollen. Likewise, there

is some cross reactivity between pine and members of the Oleaceae family (olive family), which includes privets (Ligustrum spp.) that are commonly found in the Piedmont Triad.

Symptoms from most pine pollen allergies (as well as other

tree allergies) occur in the spring when the tree pollen levels are elevated.

Interestingly, this is a distinct reaction compared to that experienced when

you put a fresh Christmas tree in your house and start having allergic rhinitis

symptoms. By the time the holiday season rolls around, tree pollen is long

gone. Reactions to Christmas trees are typically due to either late fall weed

pollens that enter the home on the tree itself or, more commonly, mold present

on the trees.

One question we often are asked when a patient is allergic

to pine is whether they can safely eat pine nuts. Pine nuts are the inner parts

of cones harvested from any one of several Pinus

species. They have been eaten as an excellent source of nutrition for over

2000 years, starting in the Mediterranean region, and contain saturated fatty

acids, potassium, phosphorus, magnesium, zinc, and vitamin B1 and B2. They are

often added to hummus as well as pesto. Consumption of pine nuts has increased

as the Mediterranean diet has taken off. Although a few cases are associated

with allergies to other tree

nuts, most patients with a pine nut allergy are monosensitized (meaning

they do NOT have allergies to other tree nuts). Thankfully, there is very

little chance of cross-reactivity between the proteins of the pine pollen and

the proteins of the pine nut. So, happy eating!

Comments

Post a Comment